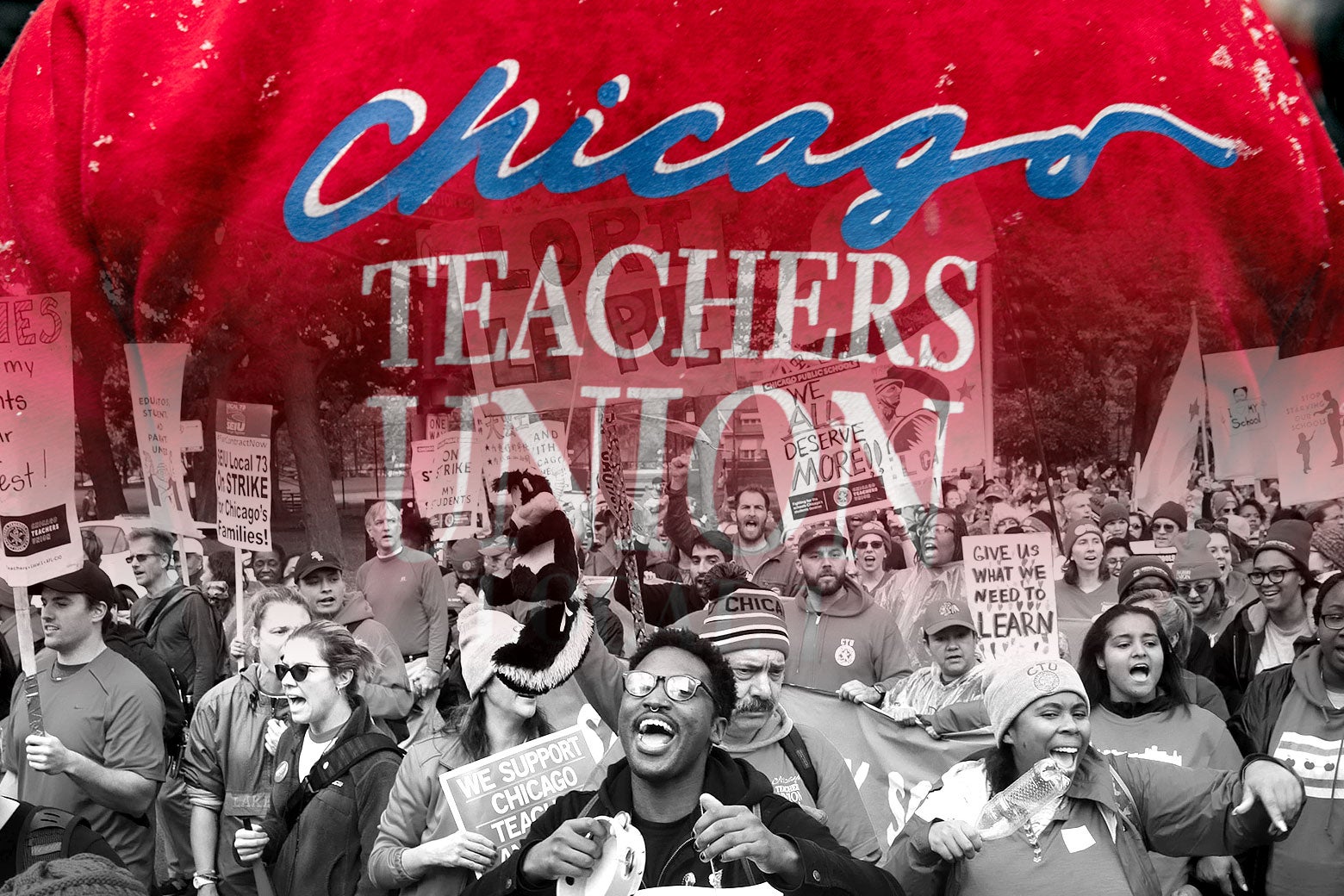

Over the past few decades, the Chicago Teachers Union has become a powerful force within city politics, growing a vast network of supporters and developing relationships with Illinois lawmakers. It has used that power to wage the same fight with nearly every Chicago mayor since the 1990s: give teachers more control over their classrooms and their contracts.

Now one of its own, CTU staff organizer and former Chicago Public Schools teacher Brandon Johnson, is running for mayor—and he’ll be facing off in the runoff election Tuesday against Paul Vallas, the former CEO of Chicago Public Schools. CTU has contributed over $1 million to Johnson’s campaign, and its role in city politics has been thrust into the spotlight as a result of the race.

The stakes of this runoff are high for CTU because the next mayor of Chicago will play a big role as the union enters a new chapter: Beginning in 2024, CTU will be allowed to collectively bargain over issues like school staffing levels, class sizes, layoffs, length of the school year, and health and safety standards for the first time. They’ll also phase into having an elected school board instead of a mayor-appointed one. These changes came after Democratic Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker signed a law handing teachers the rights that the union had been asking for for the last 25 years.

If Johnson wins Tuesday’s election, CTU will have an ally in the mayor’s office when it starts to negotiate its contract and influence CPS. But if Vallas wins, they’re facing a former CPS executive who championed charter schools, expanded standardized testing, diverted funds from teacher’s pension funds, and meted out harsh punishments for underperforming schools.

Each candidate has a very different proposal for CPS if they win the race. Vallas, who became CPS’s first mayor-appointed CEO in 1995, wants to bring back more standardized testing, give more power to principals and local leaders, and make it easier for charter schools to open. “We should be running districts of schools, not school districts,” Vallas said during a March debate with Johnson. “I really believe in radical decentralization.”

On the flip side, Johnson wants to end the model of per-pupil funding in favor of guaranteeing schools a baseline of resources that includes librarians and social workers. Johnson believes this approach would ensure schools have the necessary staffing, regardless of student enrollment, and would work toward balancing out resource inequities between schools across Chicago. “We need to overhaul the CPS funding formula so that we’re fully funding every single public school,” said Johnson during the debate. “That’s the norm, that’s the baseline. Our people deserve that.”

CTU president Stacy Davis Gates said the union supports Johnson because he brings a much-needed voice for CPS to city hall. “A middle-school teacher is at the top, and he is speaking life into the city and saying you can be safe, have a well-paying job, and your kids can go to well-resourced schools,” she told me in an interview. “He’s building a multi-generational and multi-racial movement that provides everyone a seat at the table. That’s the only thing the residents of this city desire.”

The race has certainly tightened with Vallas holding a 5-point lead over Johnson—when just weeks ago, during the first round of the mayoral election, Vallas held a 12 percent lead over Johnson.

The outsized role that CTU is playing in this year’s runoff shouldn’t be all that surprising—after all, “Chicago is the beating heart of the organized labor movement across the country,” said Tom Bowen, co-founder of political consulting firm New Chicago. The Chicago Federation of Labor says there are 300 affiliated unions that represent half a million workers throughout the city.

For decades, CTU has grown a grassroots community of local advocates, parents, teachers, and students across Chicago. Its turn to political activism was prompted by a consequential law passed in 1995 called the Chicago School Reform Amendatory Act. It singled out CPS by replacing the district’s superintendent with a CEO, giving the Chicago mayor power to appoint school board members, and limiting the issues CTU could bargain over.

It was an attempt to revamp CPS at a time when the district was performing terribly: A report by the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago revealed that in 1985 less than two-thirds of all newly admitted ninth graders would graduate from high school, and in 1987 Chicago high schools ranked in the lowest 5 percent of the country. “This bold, innovative approach should bring more accountability, better fiscal management and a higher quality of education to a system that desperately needs an overhaul,” former Republican Illinois Gov. Jim Edgar said at the time.

Illinois was joining a national trend. The Center for American Progress found that, over the past 30 years, almost 20 urban school systems across the country have moved to mayoral governance of schools, including Boston, Detroit, Philadelphia, and New York.

But CTU has maintained for decades that the law did more harm than good. Dave Stieber, a social studies teacher with CPS, wrote in a 2019 op-ed for South Side Weekly that the Amendatory Act “forbid teachers from striking over class size or teacher appointments, essentially reducing the terms of negotiations to pay and benefits.” Stieber also argued that the law ignored the conditions and lack of resources of CPS schools, creating inequities for students “so devastating that many politicians and officials in Chicago don’t even send their own children to CPS schools.”

While the Amendatory Act restricted Chicago teachers’ ability to advocate for their classrooms, the contrast in resources CPS received was growing more stark compared to schools in neighboring Evanston, Cicero, and Oak Park. “Our school communities were starved. They were underresourced,” Gates said.

The union realized it needed to get involved in city and state politics to bring those same types of resources to CPS, said Kirk Hilgendorf, legislative and political director of CTU. The union was able to gradually chip away at the Amendatory Act in small ways. Hilgendorf explained that in 2003, the union was able to change the bill’s language around collective bargaining so that certain issues became fair game. That pushed the mayor’s office to give teachers more leverage. “Our members at CTU have fought tooth and nail to make sure that they are respected as stakeholders in this city,” Gates said.

In 2008, CTU established the Caucus of Rank-and-File Educators to force Illinois lawmakers to pay attention to the issues CPS was facing. “They wanted to show how the city’s approach to education reform was a very top-down process controlled by wealthy elites in the community who had no interest in minority students,” explained Robert Bruno, a labor education professor at the University of Illinois and author of A Fight For the Soul of Public Education.

By 2012, CTU had elected a new set of union leaders, including Karen Lewis, a chemistry teacher who became president of CTU. She led the charge in catapulting the union into political activism, even while fighting brain cancer, and became a national figure in the labor and education movements before her death in 2021. “She said we had to change the political landscape in the city of Chicago to be able to get the schools Chicago students deserve,” said Hilgendorf.

In 2012, Lewis organized the first teachers’ strike Chicago had experienced in a quarter century. It lasted eight days, with over 25,000 teachers walking off the job—and CTU members won a 17.6 percent raise over four years.

That success empowered the union to lean further into politics. “When you reach out to the community in a collective bargaining struggle and you energize them, educate them and give them a voice, that’s acting politically in the best sense of the term,” said Bruno.

A few years later, CTU began endorsing candidates in local and statewide races who it believed would prioritize public education. From 2018 to 2019, the union spent $1.5 million on lobbying and other political activity. Then in 2019, the union went on strike again. It lasted 11 days and resulted in the mayor’s office agreeing to spend millions on reducing class sizes, paying for more social workers, nurses, and librarians, and increasing teacher salaries 16 percent over the next five years.

Gates, the CTU president, is confident the union’s influence is unmatched. “There is not another union in this city whose members have the numbers we have, that are as tied to the success of this city as my members are.”

But there is another union playing a role in this mayoral race: the Fraternal Order of Police. The FOP has endorsed Vallas; in an interview with the New York Times, FOP president John Catanzara threatened that if Johnson were to be elected, anywhere from 800 to 1,000 Chicago police officers would leave the force. Johnson has expressed support for efforts to defund police in the past, a stance he has since walked back, insisting that the “safest cities in America” tend to “invest in people.”

Vallas, on the other hand, has campaigned on a pro-police platform, including increasing police presence at train stations and hiring 2,300 new officers.

The mayoral hopeful has ties to the FOP that date beyond the current mayoral race—in 2020 Vallas served as a consultant to the union while it was in contract discussions with city hall. He also received heat for accepting a $5,000 campaign contribution from a retired Chicago police detective, which he said he was unaware of. Later, Vallas said his campaign donated the money, plus an additional $5,000, to Parents for Peace and Justice, a Chicago group for mothers of children killed by gun violence.

As the race has tightened, Vallas has tried to distance himself from the FOP, telling the Times, “I’m not beholden to anybody.”

Tuesday’s race is a test of both CTU’s and FOP’s political influence, but Bowen told me one thing is certain: In a Democratic stronghold like Chicago, CTU is “a force you want with you, as opposed to against you.”